Schlagwort-Archive: zzxzx

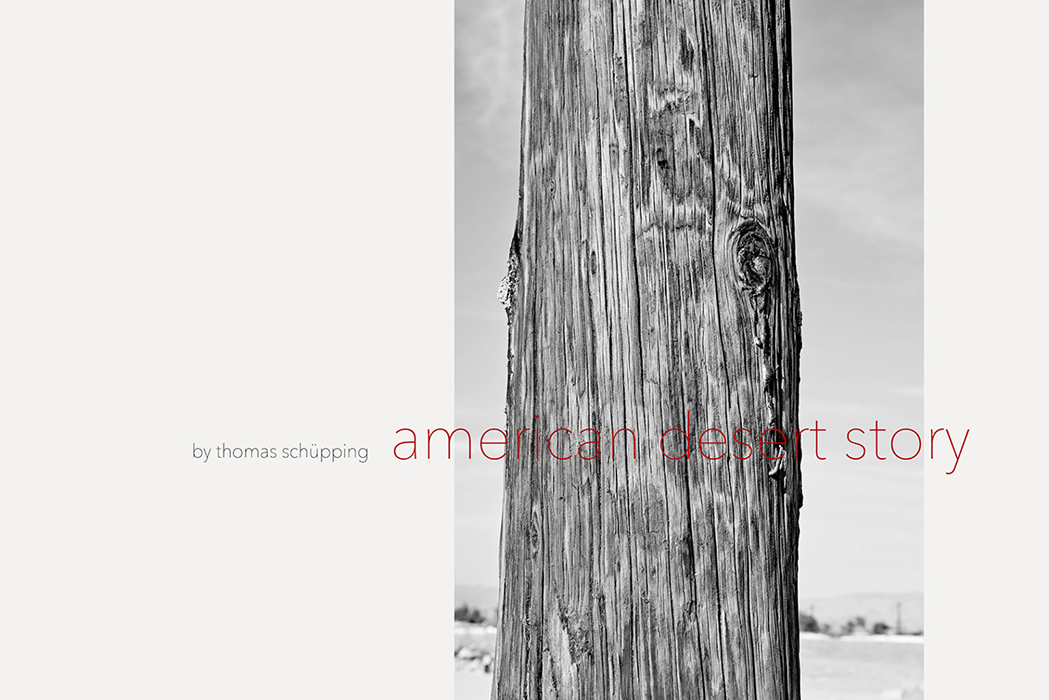

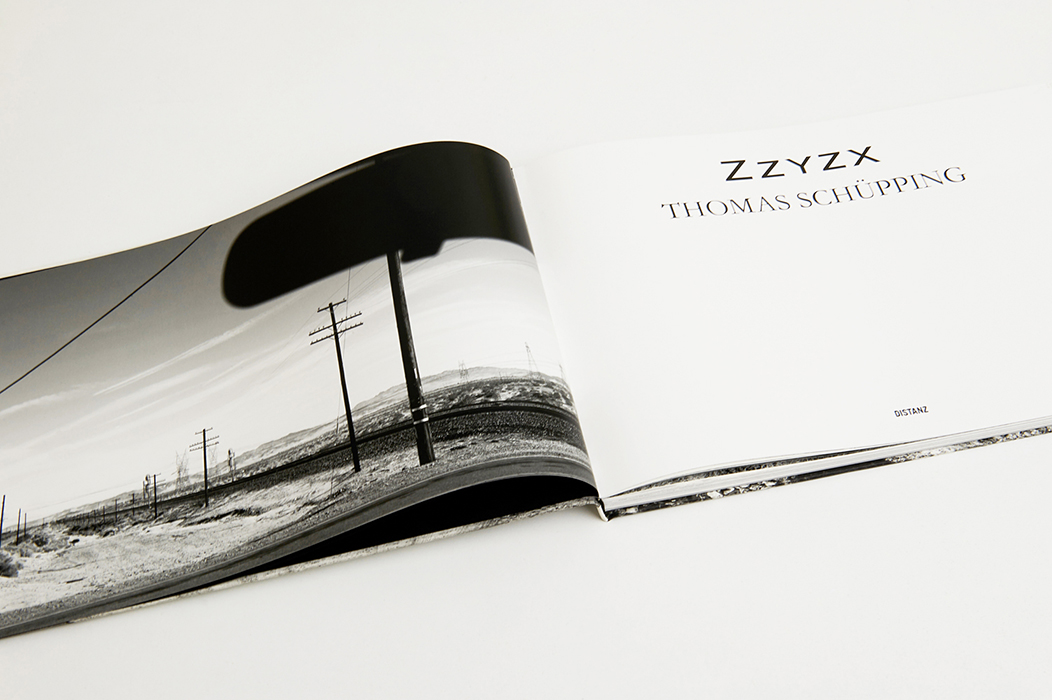

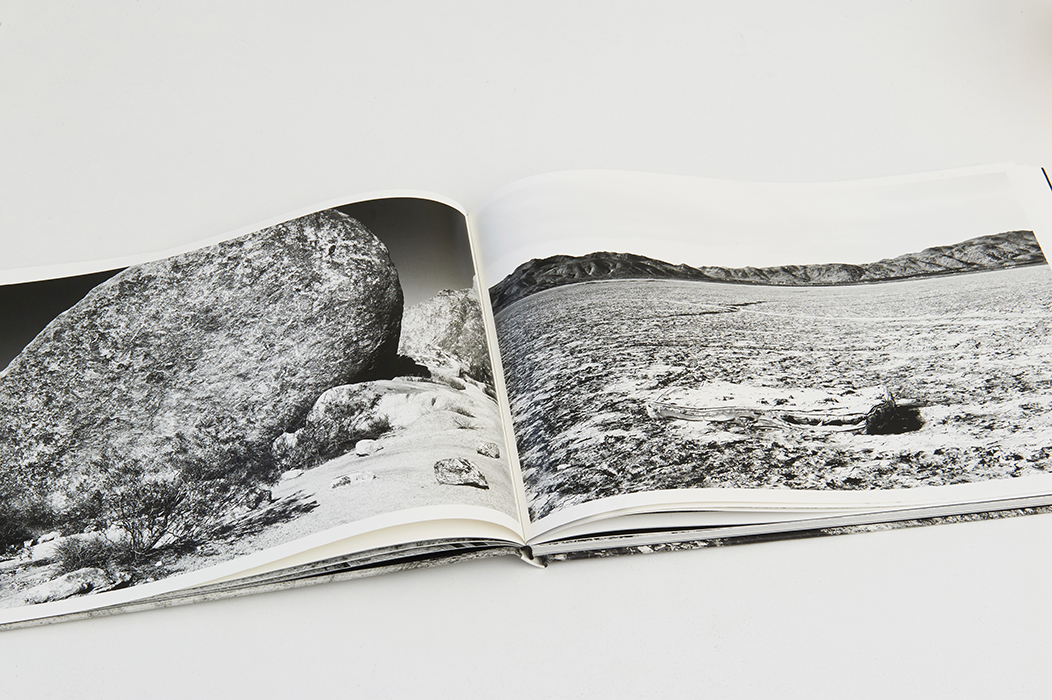

Thomas Schüpping „ZZYZX“

thomas-schüpping-zzyzx-15

thomas schüpping zzyzx

thomas schüpping norway

Thomas Schüpping Exhibition DIE GROSSE 2018 Museum Kunstpalast Düsseldorf

thomas schüpping time

thomas schüpping weithorn galerie

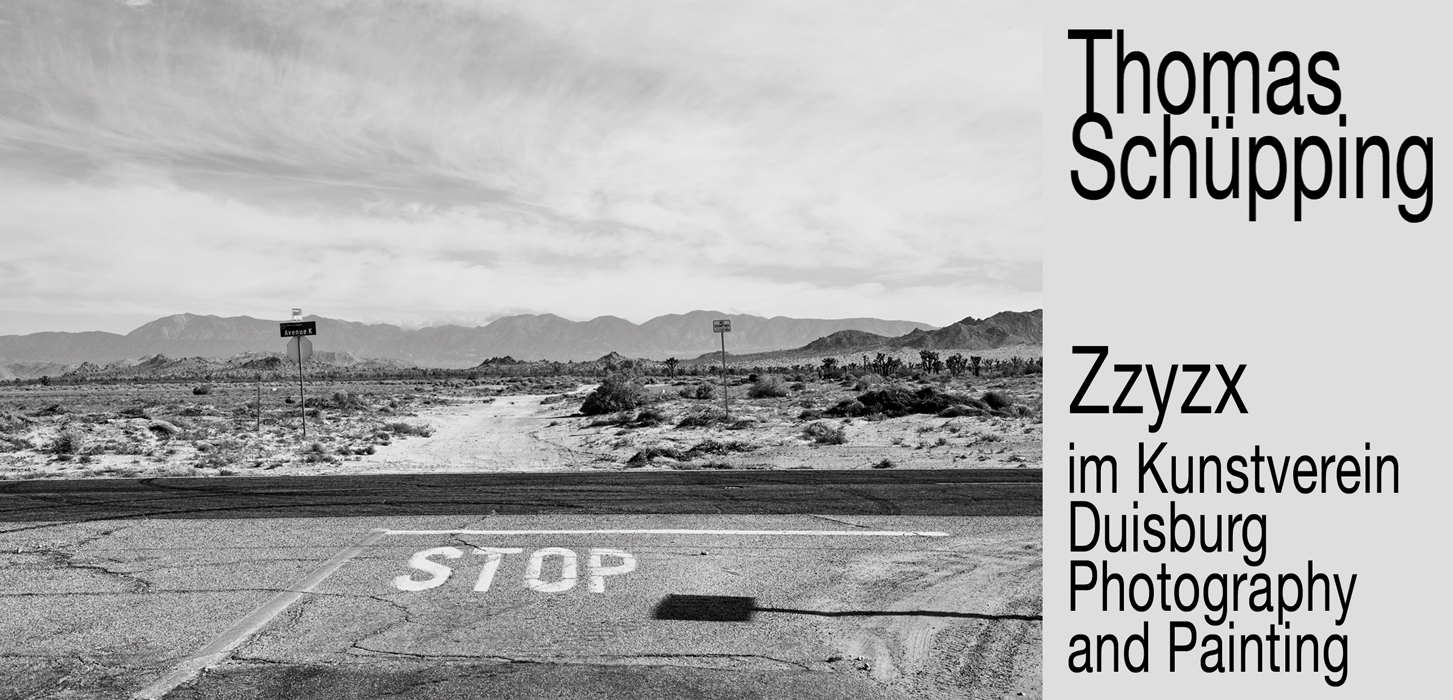

thomas schüpping exhibition „zzyzx“ kunstverein duisburg

stille landschaften zzyzx 2000-2015

Stille Landschaften

„Die Landschaft änderte sich merklich: die höhere Böschung, die sogar streckenweise die Sicht nach der einen wie nach der anderen Seite versperrte, wurde fast ununterbrochen von dichten Büschen überragt, hinter denen sich hier und da ein Kiefernstamm erhob. Bis hierher wenigstens schien alles in Ordnung zu sein.“

Alain Robbe-Grillet, Der Augenzeuge, 1955 [1]

Welchen Sinn mag es haben, Landschaften und urbane Situationen – fernab der gewohnten Umgebung, fernab jeder Sensation – fotografisch festzuhalten? Wenn nicht einmal die (bewahrende oder vermittelnde) Dokumentation das Ziel ist? Ließe sich durch solche Ausschnitte vorgefundener Realität eine Erkenntnis gewinnen, die über die Landschaft selbst oder eine äquivalente Erfahrung hinausreicht, oder sind die Fotografien Metaphern für ein Anderes? Mit Nachdruck hat Walter Benjamin auf das Defizitäre von Fotografie hingewiesen, sie als Gefahr für die synästhetische – wirkliche – Wahrnehmung empfunden und mithin einen Verlust des Sinnlichen konstatiert. Benjamin spricht vom „Hier und Jetzt des Originals“, welches seine „Echtheit“ konfiguriere. Im Hinblick auf die Natur führt er dazu wie folgt aus: „Es empfiehlt sich, den (…) für geschichtliche Gegenstände vorgeschlagenen Begriff der Aura an dem Begriff einer Aura von natürlichen Gegenständen zu illustrieren. Diese letztere definieren wir als einmalige Erscheinung einer Ferne, so nah sie sein mag. An einem Sommernachmittag ruhend einem Gebirgszug am Horizont oder einem Zweig folgen, der seinen Schatten auf den Ruhenden wirft – das heißt die Aura dieser Berge, dieses Zweiges atmen.“ [2]

Thomas Schüpping fotografiert Landschaften und urbane Situationen mit einer Intensität, die nach der Aura als authentischem Zustand des Eigentlichem fragt und den eigenen Standpunkt zwischen Präsenz und Absenz bedenkt. Er schafft Surrogate für Ursprünglichkeit und reine Schönheit.

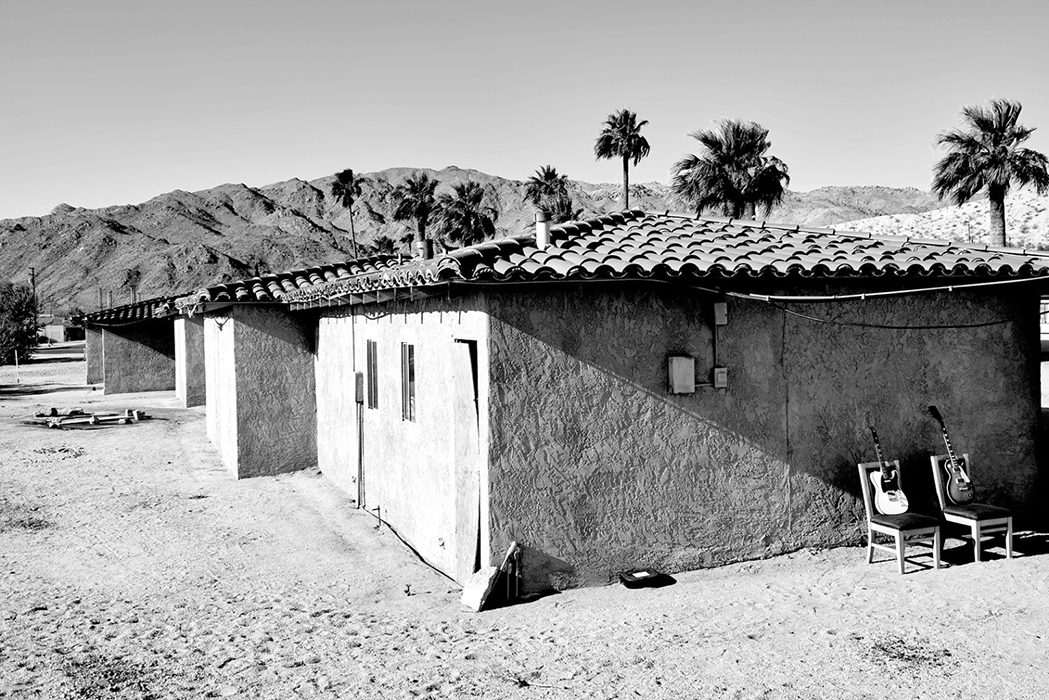

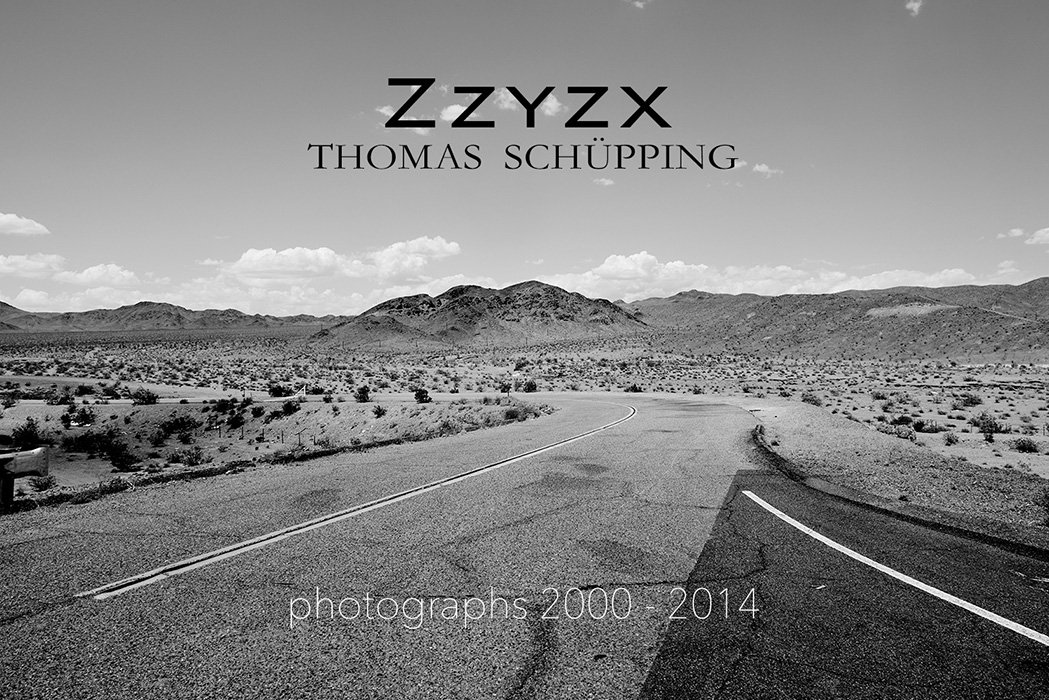

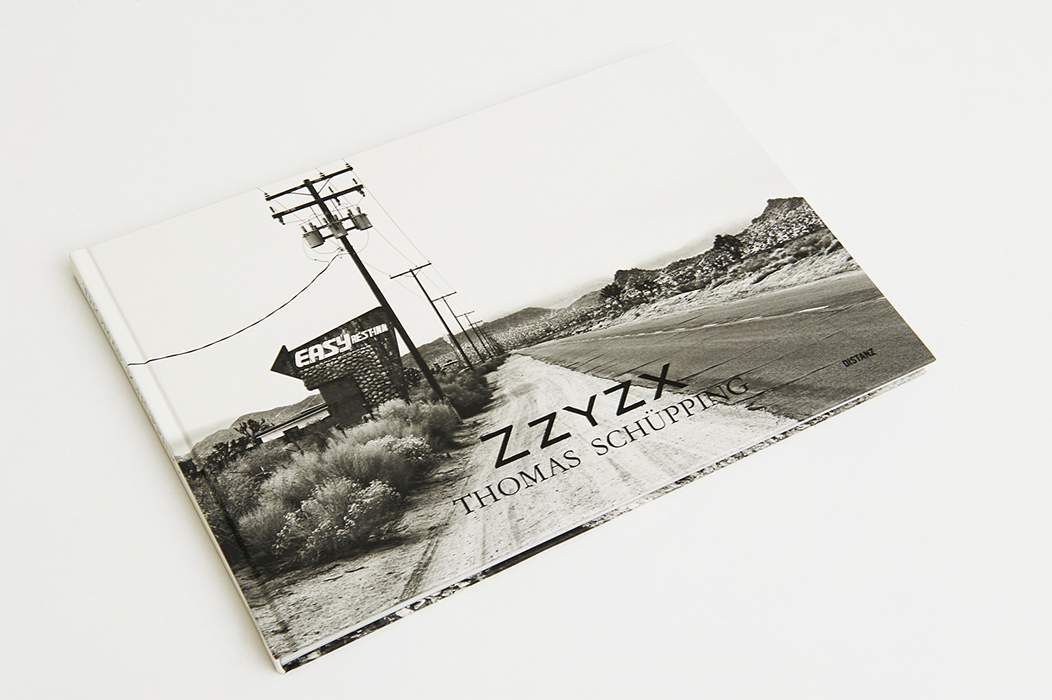

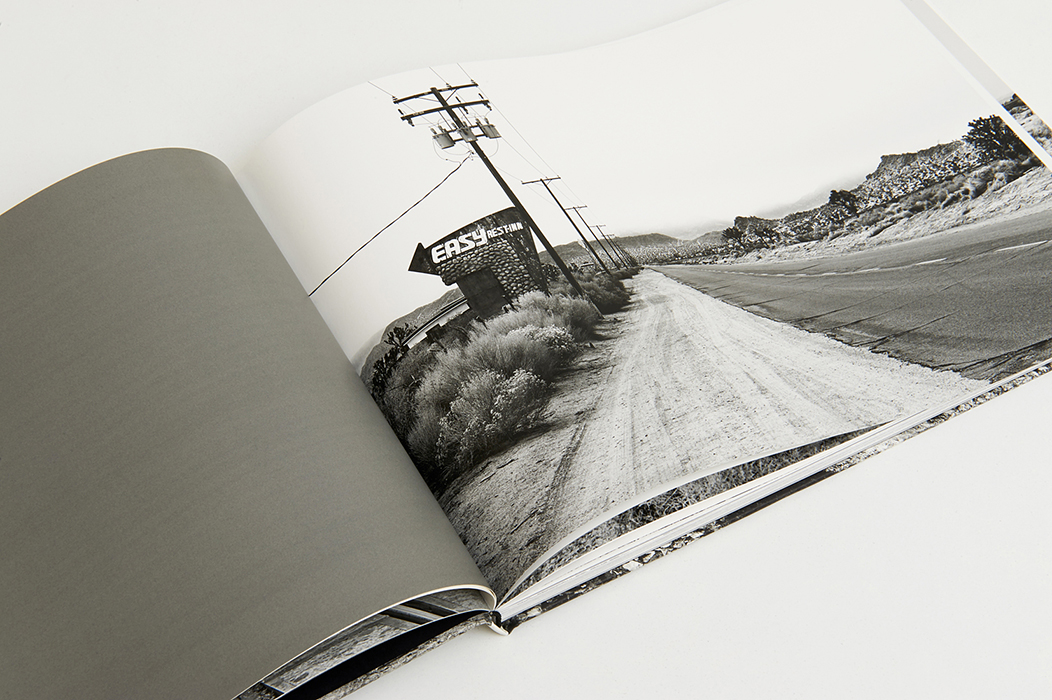

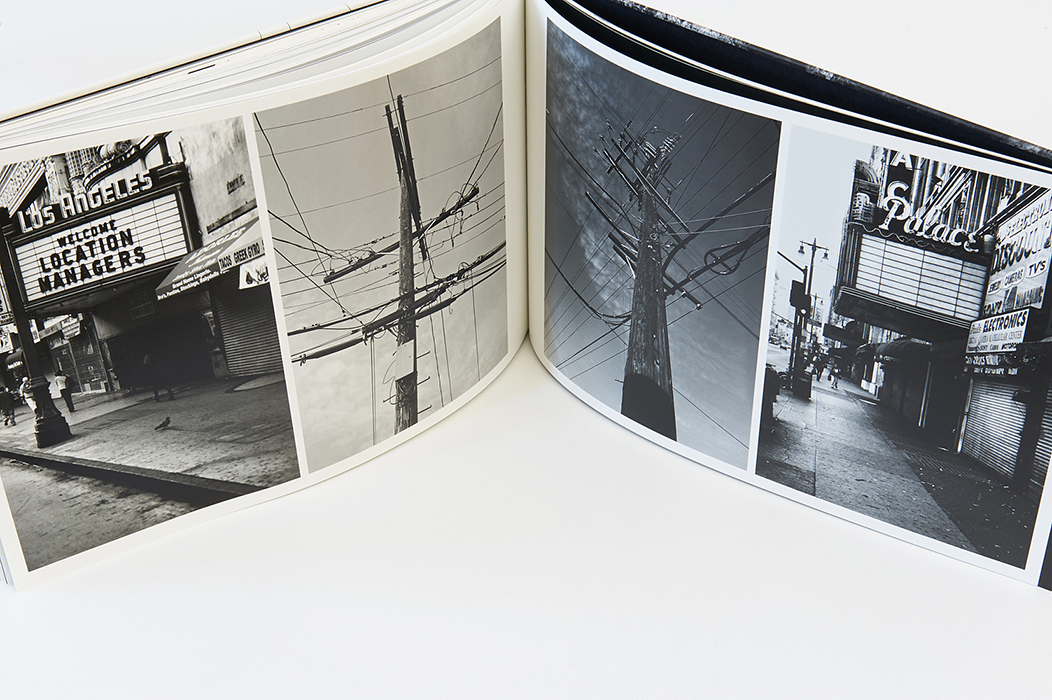

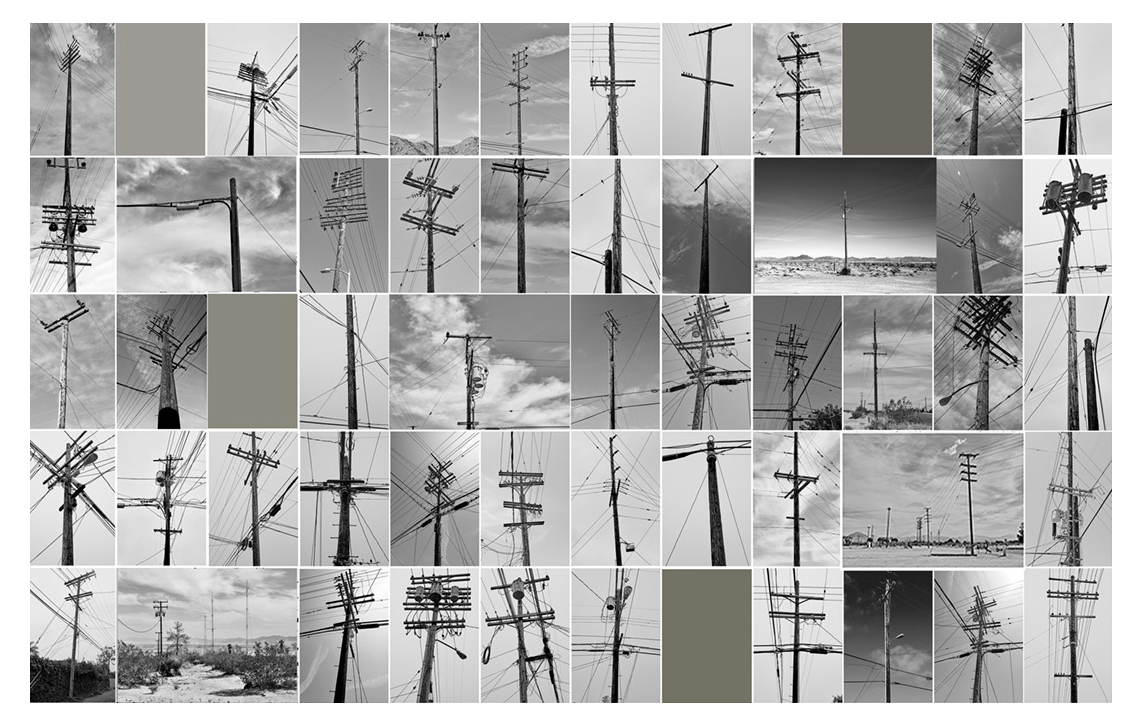

Die Fotografien, um die es hier geht, hat Schüpping sämtlich in den Vereinigten Staaten geschossen: In der Mojave-Wüste, in dem Death Valley, in Nevada und Los Angeles und zuletzt New York. In der Mehrzahl aber handelt es sich um Situationen an der Peripherie der Zivilisation, wobei die Spuren des Aufgelassenen gegenüber denen der Besiedlung überwiegen.

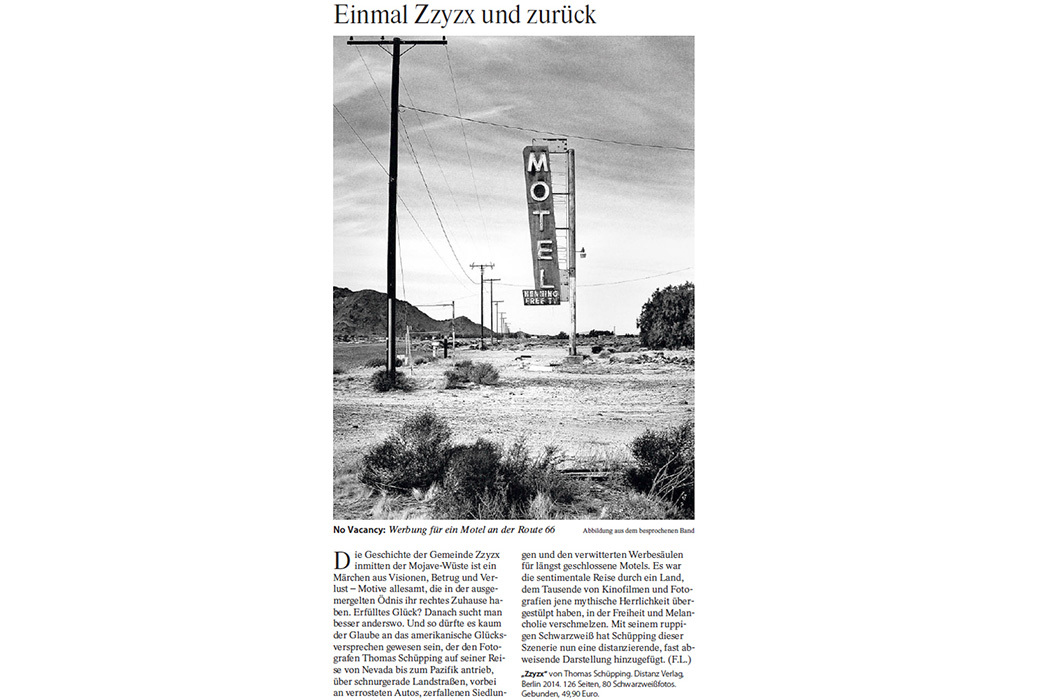

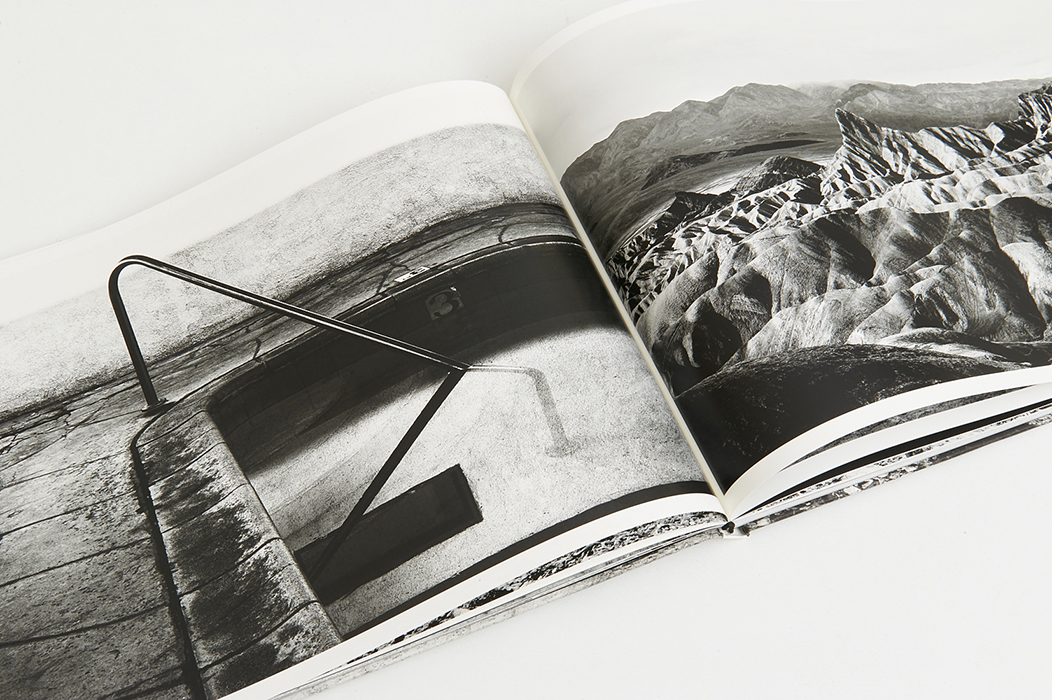

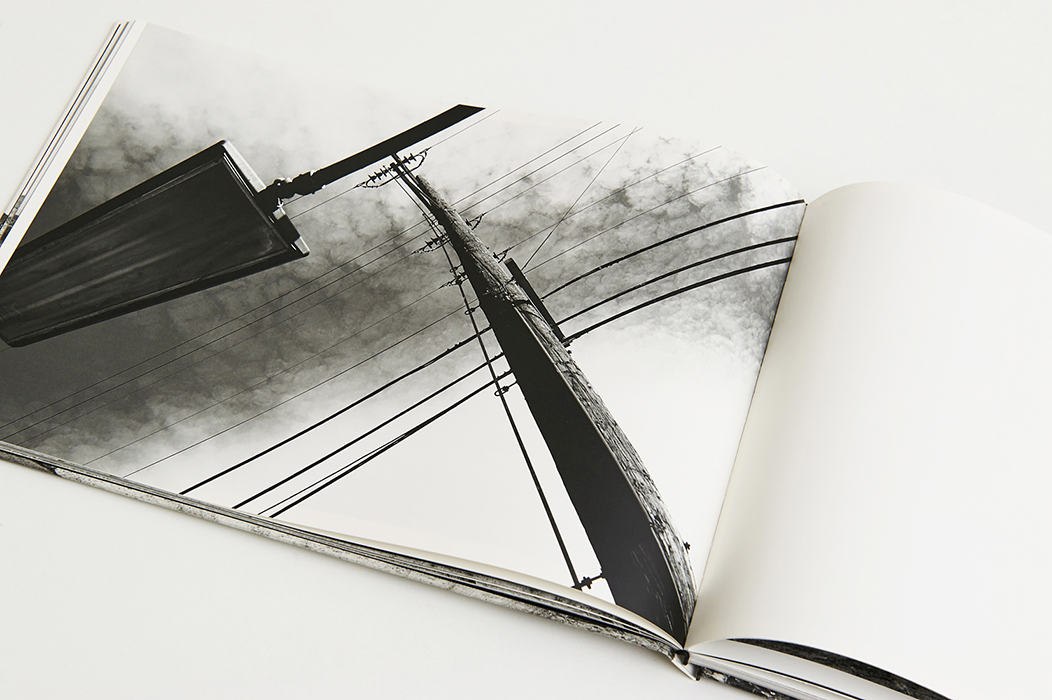

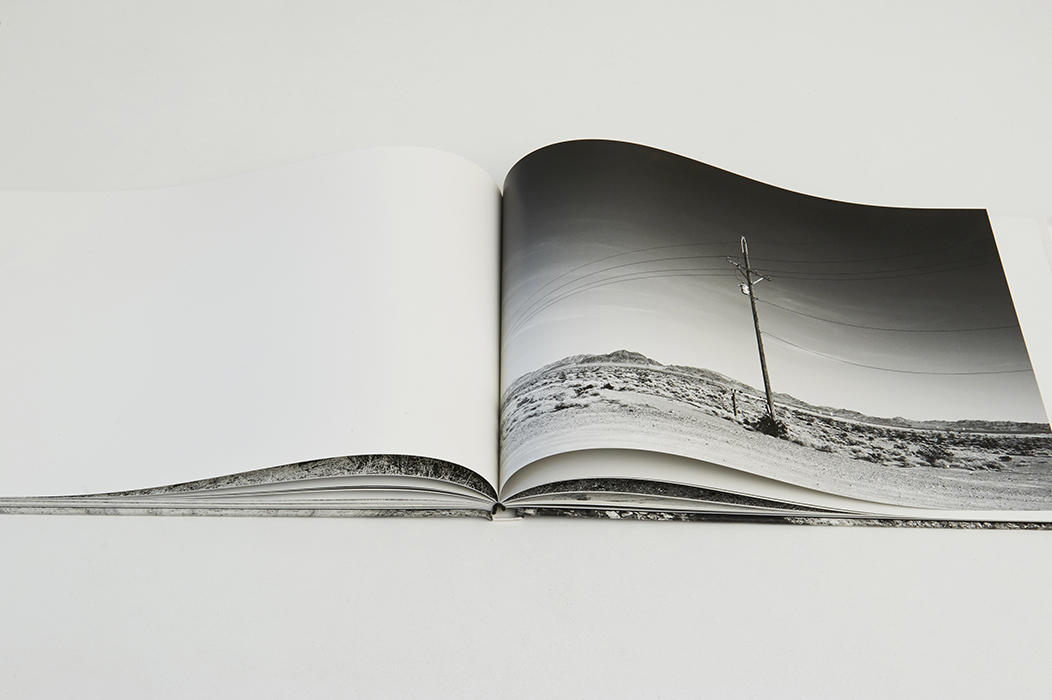

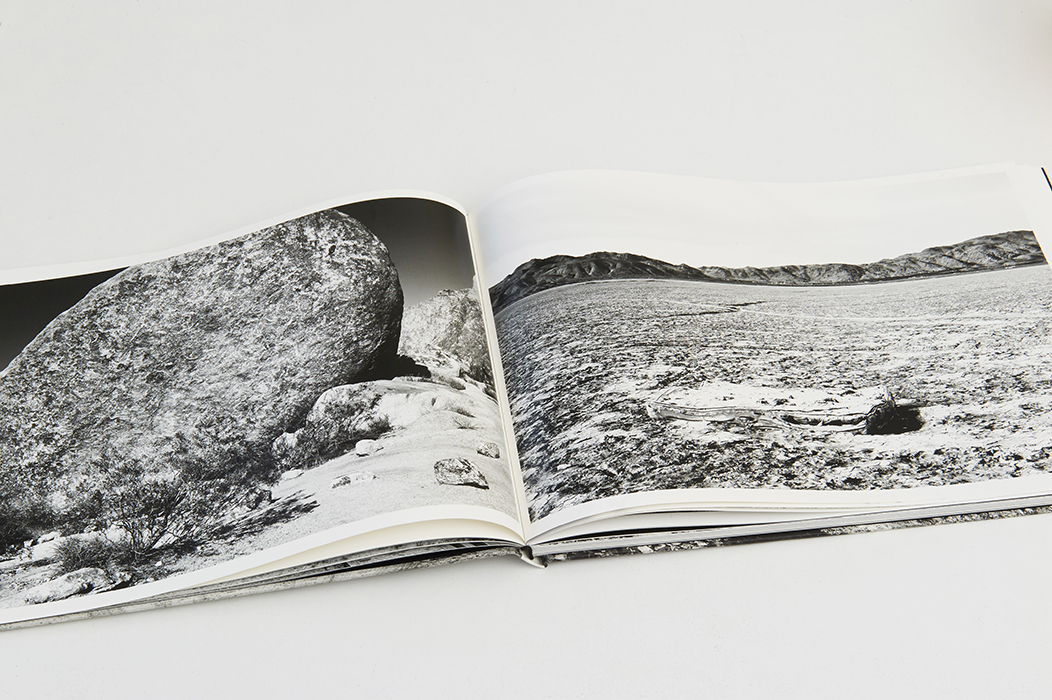

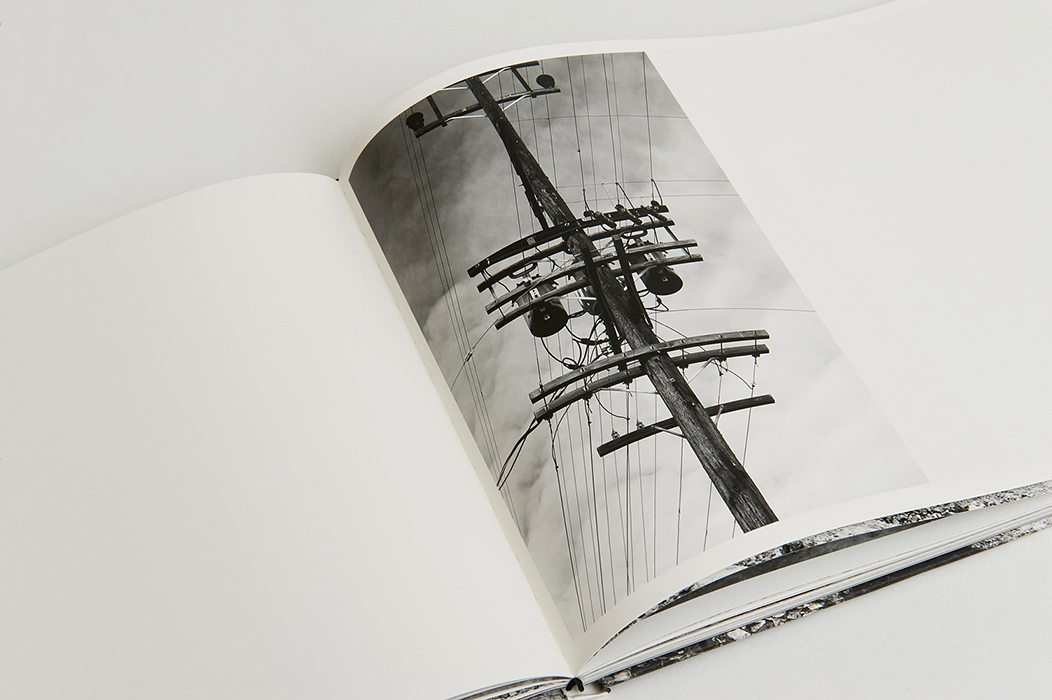

Den weitaus größten Teil nehmen die Aufnahmen in der Mojave-Wüste ein. Schüpping konzentriert sich auf den kalifornischen Teil mit Temperaturen von über 45° C im Sommer. Er verzichtet auf touristische Attraktionen zugunsten des Unverbrauchten und Selbstbestimmten. Ihm liegt am Selbstverständnis der Landschaft, die er in ihrer relativen Monotonie aufnimmt, dazu in schwarz-weiß, überwiegend im Querformat. Er hält die Vegetation in der Weitläufigkeit der Wüste fest, welche sich über das Bild hinaus fortsetzt. Mitunter verlaufen durch sie Autostraßen und Schienenstränge, die wirken, als wären sie schon immer hier gewesen. Die Spannungsmasten vermessen in ihrem Rapport die Ferne und weisen auf Elektrifizierung und Telekommunikation; aber es scheint, als wäre die Zeit irgendwann stehen geblieben und die Technik außer Betrieb. Bei einzelnen Aufnahmen rückt Schüpping konstruktive Elemente – Fremdkörper in der Natur – deutlich ins Bildzentrum, wie etwa bei dem Klettergerüst auf einem Spielplatz, den er mit dem Abstand mehrerer Jahre noch einmal fotografiert hat. Aber auch da, immer wirken die Landschaften und Gegenden, die er in der Mojave-Wüste fotografiert hat, großzügig und in ihrer Leere lapidar, unabänderlich. Zu erwähnen ist, dass Schüpping, der sich in anderen Werkgruppen dem Menschen und seinem Antlitz in Ausschließlichkeit zuwendet, bei diesen Landschaftsaufnahmen ganz auf Personen verzichtet hat. Aber beiden Bereichen liegt das gleiche Engagement zugrunde: Thomas Schüpping arbeitet das Da-Sein seiner Sujets heraus, im „Entdecken – Sehen des einen Motivs“ [3], wie er dazu sagt. Konsequenter Weise geht er bei seinen Aufnahmen in der Wüste ohne archivarische oder karthographische Absicht dem Behausten wie auch dem Verlassenen nach, den Begleiterscheinungen des Transitverkehrs, der selbst kaum intakt ist. Er zeigt Gehöfte, die von Gebüsch halb verdeckt und als Motels nur noch teilweise genutzt werden, mit ihren Billboards und Schildern. Die Straße signalisiert die Durchfahrt ohne Halt. Und sie definiert den Horizont in seiner räumlichen Dimension. „Die Gerade ist eine Vorwegnahme der Hochgeschwindigkeit: die Geradlinigkeit der Trasse zwischen zwei Polen, zwischen zwei Städten nahm die Spur der schnellen Vehikel vorweg, den Reifenabdruck der Autoreifen wie den Kondensstreifen der Düsenjets am Himmel“, schreibt Paul Virilio in seiner „Bunkerarchäologie“. [4]

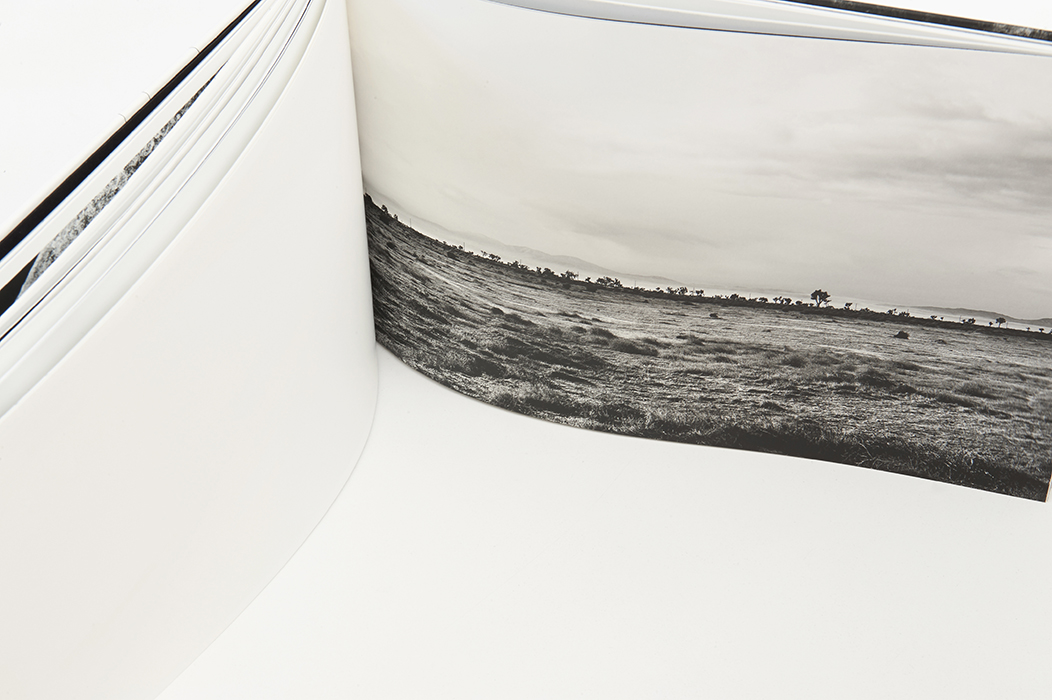

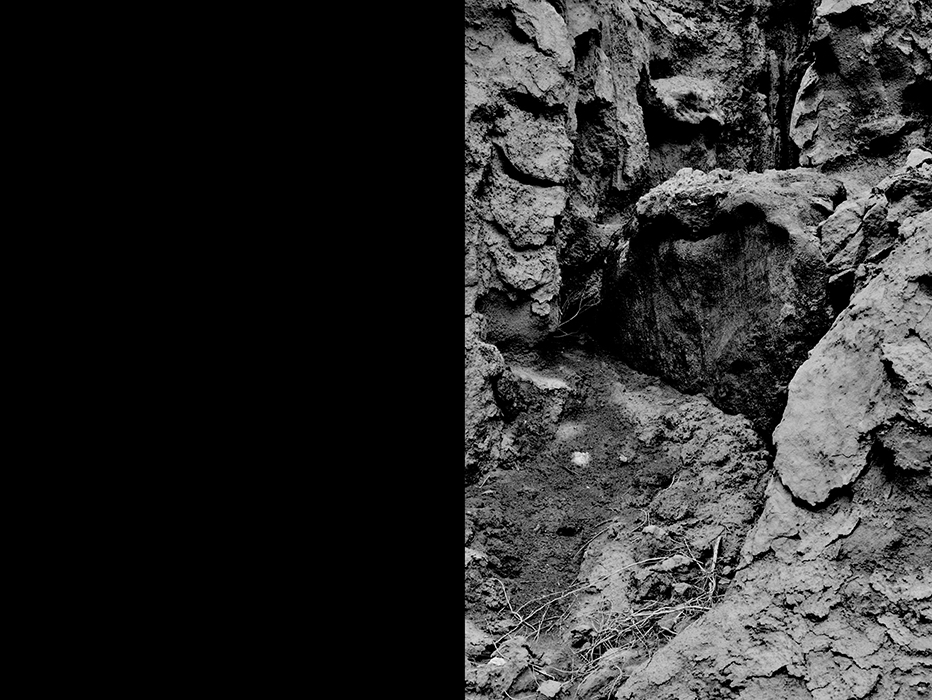

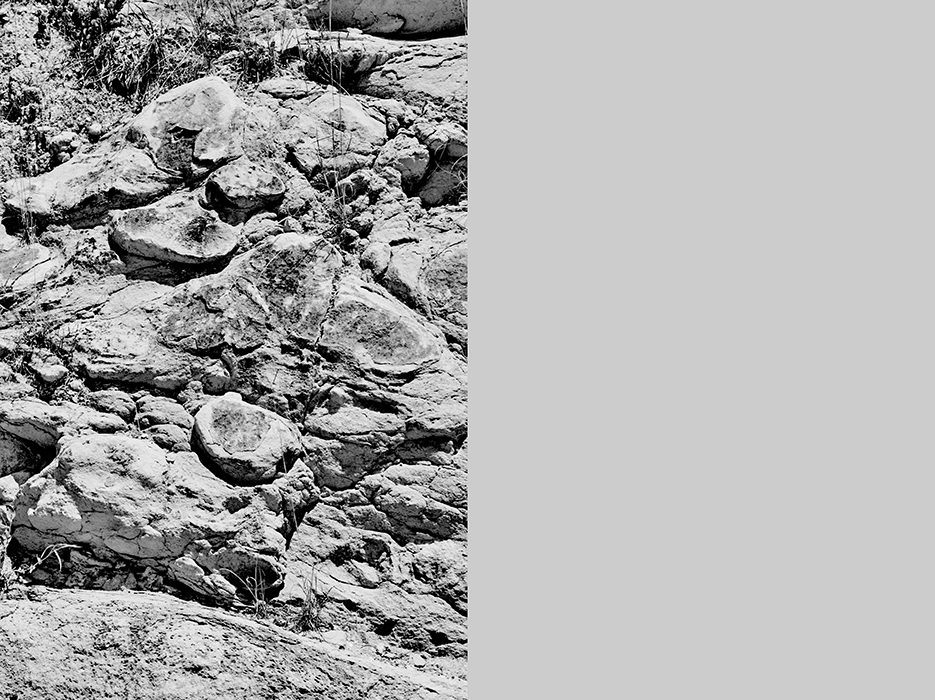

Thomas Schüpping schildert das Danach und den Verzicht. In seinen stärksten Fotografien lässt er uns die vollständige Entschleunigung spüren. Das passiert ganz ohne die Evidenz von Bewegung. Nur ganz selten ist in der Ferne ein Fahrzeug auf seiner Strecke zu sehen; einige Bilder zeigen einen Autofriedhof. Hingegen konzentriert sich die Hälfte der Aufnahmen auf die Schilderung der Wüste selbst, dort, wo sie vom Menschen unberührt ist. Thomas Schüpping wendet sich in seiner Fotografie der Gegend in ihrer gewachsenen Struktur zu; in den letzten Jahren betrifft dies besonders Bergketten und Anhöhen hinter einer weitläufigen Ebene. Sein Blick schweift von der höchsten Stelle über die Gebirge, deren Ausläufer nun wie die Pranken riesiger Urmenschen wirken. Dann wieder, bei anderen Bildern, nimmt er eine niedrige Perspektive ein, mit der er Piero della Francesca’s Untersicht in den Naturraum überträgt und dessen unabsehbare Weite betont. Im Vordergrund wachsen einzelne Büsche oder karge Baumstämme, mitunter die Joshua-Palmlilie. Schüpping notiert die Schärfe und Feingliedrigkeit der Blätter ebenso wie das Zerklüftete der Gesteinsformationen. Die Kamera hält jede Erhebung und jeden Riss in der trockenen Ebene fest – sachlich und präzise, dabei in tonaler Nuancierung, vermitteln diese fotografischen Schilderungen die Natur in ihrer Selbstbehauptung und spröden Sinnlichkeit.

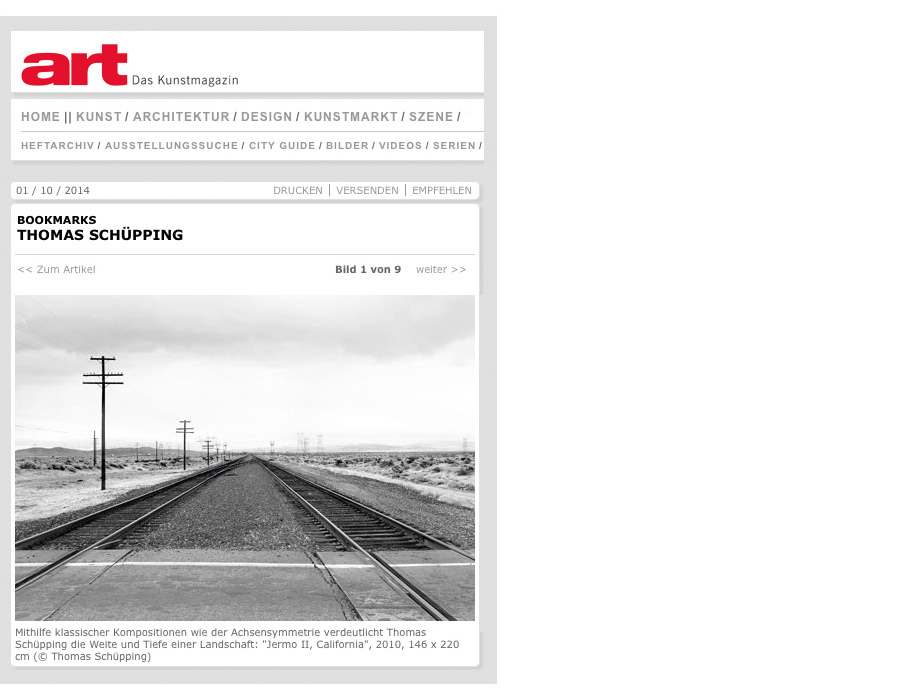

Schüpping organisiert seine Aufnahmen nach klassischen Verfahren. Er arbeitet mit der Achsensymmetrie, etwa wenn er das Gleisbett von vorne in die Tiefe führt und so die Landschaft teilt. Und er komponiert seine Fotografien nach dem Goldenen Schnitt in einer konstruktiven Anlage; im Gespräch beruft er sich auf die Traditionen des Bauhaus. In seinen Aufnahmen verlaufen die Schichtungen der Natur häufig leicht schräg vom linken zum rechten Bildrand, wodurch eine unterschwellige Dynamik entsteht und die Syntax der Region augenscheinlich wird. Die konzentrierte Stilllegung in der panoramatischen Überschau und das demokratische visuelle Abtasten sind innerhalb der Landschaftsfotografie von Thomas Schüpping nicht voneinander zu trennen. Erinnert dieser Wechsel von Nähe zu Ferne, der keiner ist, nicht auch an die Wahrnehmung der Maler zwischen Klassizismus und Romantik, die nach Italien aufbrachen und die Alpen überquerten und auf diese Weise noch zu Komplizen der Geologen wurden, etwa Caspar Wolf und Joseph Anton Koch?

Schüpping erfasst die Landschaft in dem Sinne, dass er Augenzeuge ist, alle Dinge mit der gleichen Ernsthaftigkeit registriert und auf diese Weise die natürliche Verfasstheit bannt – unter den Auspizien, dass sie sich permanent wandelt und nie ganz zu erfassen ist. Er wählt die „klassische“ Fotografie an Ort und Stelle zur Erfahrung der Landschaft in Zeiten, in denen jeder Stein vom Weltraum aus digital gesichert, vermessen und ausgewertet wird. Er führt die Natur wieder der direkten Aneignung zu: als unbekanntes Terrain, als Welt ohne Menschen. Aber Schüpping liegt nicht am aufklärerischen Impetus eines Robert Adams, bei dem einzelne Sujets zu Zeugnissen und mithin Denkmälern werden. Vielmehr behält er sich auf seinen Fahrten das Planlose vor, ist ausschließlich und interessiert sich gerade nicht für die Eingriffe der Zivilisation oder für geographische Prozesse in der Natur. Schon das unterscheidet ihn auch von den Nachfolgern der New Topographic Movement. Er formuliert das vermeintlich ewig Gleiche und das schier Unendliche, und er wählt dazu die Textur des Kargen. Und er zeigt, dass diese „gewöhnlichen“, unspektakulären Orte ganz und gar nicht „leer“ sind, es aber der ausgiebigen Hinwendung bedarf, um ihre Vielschichtigkeit zu ahnen. In einem komplexen Prozess des Positionierens, Schauens und Wartens auf das rechte Licht wird das Erlebnis hier zur Einsicht. „Wir nehmen wahr – wir sehen. Wir sehen mit unseren Augen, und wir sehen mit unserem Geist. Wir wollen die Wahrheit über das Leben und alles Schöne sehen. Sie sind beide für uns ein großes Geheimnis“ [5], schreibt Agnes Martin, und Thomas Schüpping würde dies gewiss sofort unterschreiben.

Thomas Hirsch

[1] A. Robbe-Grillet, „Der Augenzeuge“, 1955, Frankfurt/M.: Suhrkamp, 1986, S. 175.

[2] W. Benjamin, „Das Kunstwerk im Zeitalter seiner technischen Reproduzierbarkeit“, 1936, Frankfurt/M.: Suhrkamp, 1977, S. 14f.

[3] Gespräch mit Thomas Schüpping im Atelier in Düsseldorf, 26. März 2013.

[4] Paul Virilio, „Bunkerarchäologie“, 1991, München, Wien: Carl Hanser Verlag, 1992, S. 19.

[5] Agnes Martin, „Ruhe und Stille in der Kunst“, 1974 / 1992, in: Dieter Schwarz (Ed.), Agnes Martin, Writings, 6. Aufl., Ostfildern-Ruit: Hatje Cantz, 2005, S. 91.

silent landscapes zzyzx 2000-2015

https://www.thomasschuepping.de/uebersicht.html

Silent Landscapes

„The landscape changed perceptibly: the higher embankment, which even obscured what was on either side of the road in some places, was lined with a virtually unbroken hedge of thick bushes behind which rose the occasional trunk of a pine tree. This far, at least, everything seemed to be in order.”

Alain Robbe-Grillet, The Voyeur, 1955 [1]

What sense might there be in photographically capturing landscapes and urban settings—far from the usual environment, far from any attraction – if (preserving or mediating) documentation is not even the goal? Is a recognition that stretches out over the landscape itself, or an equivalent experience, achieved through such extracts of found reality? Or are the photographs metaphors for something else? Walter Benjamin had emphasized the shortcomings of photography, finding it a danger to the synaesthetic – real-perception, and thus establishing a loss of sensuousness.

Benjamin speaks of the “here and now of the original” which configures its “authenticity.” In regards to nature he explains as follows: “The concept of aura (…) with reference to historical objects may usefully be illustrated with reference to the aura of natural ones. We define the aura of the latter as the unique phenomenon of a distance, however close it may be. If, while resting on a summer afternoon, you follow with your eyes a mountain range on the horizon or a branch which casts its shadow over you, you experience the aura of those mountains, of that branch.” [2]

Thomas Schüpping photographs landscapes and urban settings with an intensity that questions the aura as the authentic state of the real and considers its own standpoint between presence and absence. He creates surrogates for originality and pure beauty.

The photographs dealt with here were all shot in the United States: in the Mojave Desert, Death Valley, Nevada, and Los Angeles. They are almost always settings on the periphery of civilization, where the traces of abandonment predominate those of settlement.

The photographs in the Mojave Desert make up by far the largest share. Schüpping focuses on the Californian section of the desert where temperatures in the summer reach over 110º F (45º C). He avoids tourist attractions in favor of the untouched and the self-determined. A self-understanding of the landscape, which he photographs in its relative monotony in black and white, and usually in landscape format, is in his interest. He captures the vegetation in the vastness of the desert that continues beyond the image. Now and then highways and railroads course through, seeming as though they were always there. The high-voltage towers measure the distance in their rapport, and reference electrification and telecommunication; yet it seems as though time stands still and the technology is out of service. In individual photos Schüpping places constructed elements – foreign bodies in nature – clearly as the focus of the image, like the jungle gym in a playground, which he photographed again after an interval of several years. But there again, the landscapes and surroundings he photographs in the Mojave Desert always seem generous and straightforward in their emptiness, unchanging. Worth noting is that while most of the landscape photos here do without human subjects, in several other groups of works Schüpping turns his attention to people and faces exclusively. But both areas form the basis of the same engagement: Thomas Schüpping carves out the being-there of his subjects in, as he says, the “discovery – the seeing of the one motif.” [3] Without archival or cartographic intention in his photographs in the desert, he consistently pursues the inhabited as well as the abandoned, the side effect of transport traffic which itself is hardly intact. He shows rural architecture half hidden in bushes and only still partly used as motels, with their billboards and signs. The road signals the non-stop passage through – and it defines the horizon in its spatial dimension. “The straight line prefigures high speed: the rectitude of the mark between two poles, between two cities, anticipated the tracing of high-speed vehicles, automobile tire tracks, as well as the trail of jet exhaust gasses in the sky,” writes Paul Virilio in his book “Bunker Archeology.“ [4]

Thomas Schüpping depicts the hereafter and abandonment. In his strongest photographs he allows us the feeling of full deceleration. This happens entirely without the evidence of movement. Only very seldom is a vehicle seen driving in the distance; some images show a graveyard of cars. In contrast, half of the photographs are focused on the portrayal of the desert itself, in the places where it remains untouched by humans. In his photography Schüpping turns to the natural texture of the region; in recent years particularly mountain ranges and hills behind a vast plain. His gaze wanders from the highest point on the mountains, their foothills seeming like the paws of giant prehistoric men. Then again in other images he takes a lower perspective, carrying over the low-set view of Piero della Francesca into nature, emphasizing its indefinite expanse. In the foreground single bushes or barren tree trunks grow, here and there is a Joshua tree. Schüpping records the sharpness and intricacy of the leaves as well as the rugged rock formations. The camera captures every projection and every crack in the dry plain – factual and precise, while tonally nuanced, these photographic depictions convey nature in its assertiveness and brittle sensuousness.

Schüpping organizes his photographs according to a classic method. He works with the axis of symmetry, for instance, extending the railroad track bed from the foreground deep into the distance and in this way dividing the landscape. He composes his photographs according to the Golden Ratio in a constructive arrangement; in conversation he refers to the tradition of the Bauhaus. In his photographs the natural stratifications often run at a slight angle from the left edge of the image to the right, creating a subliminal dynamic and revealing the syntax of the region. A concentrated suspension in the panoramic overview and a democratic visual sampling are inextricably linked in the landscape photographs of Thomas Schüpping. Does this exchange from nearness to distance, though it is neither, recall not also the perception of the painters between classicism and romanticism who went off to Italy, crossing the Alps and, in this way, were even accomplices of geologists, like Caspar Wolf and Joseph Anton Koch?

Schüpping records the landscape in the sense that he is a witness, registering everything with the same seriousness and, in so doing, captures the natural condition – under the auspices that it is constantly changing and never quite able to be fully grasped. He chooses this “classical” photography on site and place to experience the landscape in times in which every stone can be digitally retained, measured, and evaluated from space. He redirects nature to immediate acquisition: as an unknown terrain, as a world without people. But for Schüpping it is the enlightening impetus of a Robert Adams, for whom individual subjects become witnesses and thus monuments. Rather he retains a haphazardness on his journeys, unrestricted and interested in not just the intervention of civilization or the geographic processes in nature.

This separates him from the followers of the New Topographic movement. He formulates the seemingly eternal sameness and the almost infinite, and chooses as well the texture of this austerity. He shows that these “ordinary,” unspectacular places are not totally “empty,” but require unstinting attention to divine their complexity. In an intricate process of positioning, looking, and waiting for the right light, the experience is here for inspection. “We perceive – We see. We see with our eyes and we see with our minds. We want to see the truth about life and all of beauty. Both are a great mystery to us,” [5] writes Agnes Martin, and to this Thomas Schüpping would surely subscribe.

Thomas Hirsch

[1] Alain Robbe-Grillet, “The Voyeur,“ 1955, English edition, translated by Richard Howard, New York, 1958.

[2] Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,“ 1936, English edition, translated by Harry Zohn, New York, 1969.

[3] In conversation with Thomas Schüpping in his studio in Düsseldorf, March 26, 2013

[4] Paul Virilio, “Bunker Archeology,“ New York, 1994.

[5] Agnes Martin, “The Still and Silent in Art,“ 1974 / 1992, in: Dieter Schwarz (ed.), Agnes Martin, Writings, 6th edition, Ostfildern-Ruit, 2005.